Chapter 15 of the biography “Ramana Maharshi And The Path Of Self-Knowledge” written by Arthur Osborne

<

On the whole the devotees were very normal people. By no means all were scholars or intellectuals. In fact, it not infrequently happened that some intellectual preoccupied with his theories would fail to perceive the living Truth and drift away, while some simple person would remain and worship and, by his sincerity, draw on himself the Grace of Bhagavan. Because self enquiry is called Jnana-marga, the Path of Knowledge, it is sometimes supposed that only intellectuals can follow it, but what is meant is understanding of the heart, not theoretical knowledge. Theoretical or doctrinal knowledge may be a help but it may equally well be a hindrance.

Sri Bhagavan wrote: “What avails the learning of those who do not seek to wipe out the letters of fate by asking, ‘Whence is the birth of us who know the letters?’ They have made themselves like a gramophone. What else are they, Oh Arunachala? It is the unlearned who are saved rather than those whose ego has not subsided despite their learning” (Supplementary Forty Verses, vv. 35-36). The words about wiping out the letters of fate refer to the Hindu conception of a man’s destiny being written upon his brow and mean the same, therefore, as transcending one’s karma. They are a further confirmation of what was said in Chapter Five, that the doctrine of destiny does not take away the possibility of effort, or indeed the necessity for it.

Learning was not condemned in itself, just as material wealth and psychic powers were not; only, with all three alike, the desire for them and preoccupation with them were condemned as blinding a man and distracting him from the true goal. As is stated about psychic powers in an ancient text already quoted, they are like ropes to tether a beast. It was sincerity that was required, not brilliance; understanding, not theory; humility, not mental pride. Particularly when songs were sung in the hall one would see this, noticing the perfunctory interest Sri Bhagavan might show to some celebrity and the radiance of his Grace showered on one who sang with true devotion even if with little skill.

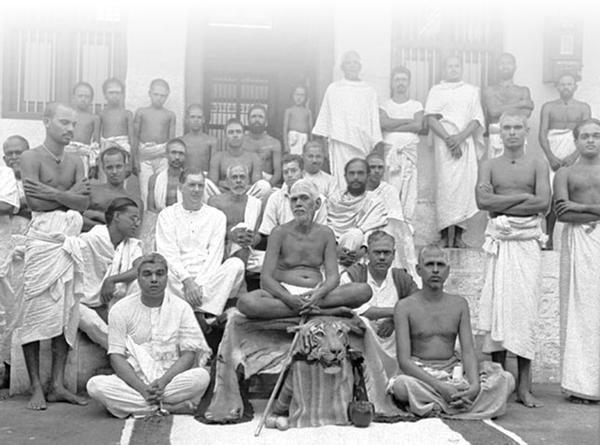

Naturally, Hindus were the most numerous among the devotees, but there were many others also. None did more to spread knowledge of Sri Bhagavan through the world than Paul Brunton with his book, A Search in Secret India.

Among the permanent residents in or around the Ashram in later years were Major Chadwick, large, military and benevolent, with a booming voice; Mrs. Taleyarkhan, a Parsi lady with an imperious nature and the air of a grande dame; S.S. Cohen from Iraq, quiet and unobtrusive; Dr. Hafiz Syed, a retired professor of Persian, with something of the old-world charm of a Muslim aristocrat. Visitors came for longer or shorter periods from America, France, Germany, Holland, Czechoslovakia, Poland, from many lands.

Viswanathan, a younger relative of Sri Bhagavan, came in 1923 as a nineteen-year-old youth and remained. It was not his first visit, but this time as soon as he entered the hall Sri Bhagavan asked him, “Have you taken leave of your parents?”

The question was a recognition that this time he had come to stay. He admitted that, like Sri Bhagavan himself, he had simply left a note, not saying where he was going. Sri Bhagavan made him write a letter, but in any case the youth’s father guessed where he had gone and came to talk it over. He had an open mind about it. He had heard glowing reports of the Swami but he had known him as a younger relative in the days when he was Venkataraman and naturally found it hard to conceive of him as Divine. Coming into the Presence, his body quivered with awe and he had fallen on his face before he knew it had happened.

“I see nothing of the old Venkataraman here!” he exclaimed.

And Sri Bhagavan laughed: “Oh, that fellow! He disappeared long ago.”

Speaking to Viswanathan in his usual humorous way, Sri Bhagavan once said, “At least you knew Sanskrit when you left home; when I left home I knew nothing.”

There were others also who knew Sanskrit and had studied the Scriptures, among them the retired Professor Munagala Venkatramiah (compiler of Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi), who lived as a sadhu and for some years kept an Ashram diary, and the schoolmaster Sundaresa Aiyar, already referred to, who carried on his profession in Tiruvannamalai.

In the same year as Viswanathan, Muruganar also came, one of the foremost of Tamil poets. Sri Bhagavan himself would sometimes refer to his poems or have them read out. It was he who put together the Forty Verses and made a book of them, and he has also written an outstanding Tamil commentary on them. The musician ManavasiRamaswami Aiyar is a still older devotee. Senior in years to Sri Bhagavan, he came to him first in 1907. He also composed beautiful songs in praise of the Master.

Ramaswami Pillai came as a youth straight from college in 1911 and stayed. Like Viswanathan and Muruganar, he remained a sadhu; however, in his case the path was rather through devotion and service. Once in 1947 Sri Bhagavan injured his foot on a stone during his daily walk on the Hill. Next day Ramaswami Pillai, grey haired already but still robust, set out to make steps and a path up the hillside. Single-handed he worked, from dawn to dusk, day after day until the path was finished, the edges firmly shored up with stone, steps chiselled out where there was a rock platform, built up where there was an earthen slope. It was well and thoroughly constructed, so thoroughly that the monsoon rains have not washed it away since; however, it has not been kept in repair because shortly after it was finished Sri Bhagavan’s failing health compelled him to give up his walks on the Hill.

Ranga Aiyar, the old school friend already referred to, never settled down at Tiruvannamalai but he and his family used to come on frequent visits. He had studied in the same class as Sri Bhagavan and had played and wrestled with him, and he always enjoyed great freedom in talking and joking. Coming in the early Virupaksha days to see what his old friend looked like as a Swami, he immediately recognised that he stood before Divinity. Not so his elder brother, Mani. He stood looking scornfully at the young Swami he had known as a junior at school. Sri Bhagavan returned the look and under the impact Mani fell at his feet. After that he also became a devotee. One of Ranga Aiyar’s sons wrote a long Tamil poem celebrating the ‘marriage’ of Sri Bhagavan with Divine Knowledge (Jnana).

A large part of Maharshi’s Gospel was compiled from conversations with the Polish refugee, M. Frydman. Two Polish ladies are well-known figures at the Ashram. When Mrs. Noye had to return to her native America she could not restrain her tears. Sri Bhagavan consoled her: “Why do you weep? I am with you wherever you go.”

It is true of all Bhagavan’s devotees. He is always with them; if they remember him he will remember them; even if they let go of him he will not let go of them, nevertheless to have it said to one personally was a great blessing.

My three children, the only European children at Tiruvannamalai, were conspicuous among the devotees. One evening in December 1946 Sri Bhagavan initiated the two elder of them into meditation, and if their efforts to describe it fail, so do those of older people. Kitty, who was ten, wrote: “When I was sitting in the hall this evening Bhagavan smiled at me and I shut my eyes and began to meditate. As soon as I shut my eyes I felt very happy and felt that Bhagavan was very, very near to me and very real and that he was in me. It wasn’t like being happy and excited about anything. I don’t know what to say, simply very happy and that Bhagavan is so lovely.”

And Adam, who was seven, wrote, “When I was sitting in the hall I didn’t feel happy so I began to pray and I felt very happy, but not like having a new toy, just loving Bhagavan and everyone.”

Not that children sat often or long hours in the hall. When they felt like it they sat; more often they played about.

When Frania, the youngest child, was seven the other two were talking about their friends and she, having no real friends yet but not wanting to be left out, said that Dr. Syed was the best friend she had in the world. Sri Bhagavan was told.

“Ah?” he replied, with perfunctory interest.

And her mother said, ‘What about Bhagavan?’

“Ah?” This time he turned his head and showed real interest.

“Frania said, ‘Bhagavan is not in the world’.”

“Ah!” He sat upright with an expression of delight, placing his forefinger against the side of his nose in a manner he had when showing surprise. He translated the story into Tamil and repeated it delightedly to others who entered the hall.

Later Dr. Syed asked the child where Bhagavan was if not in the world, and she replied, “He is everywhere.”

Still he continued in Quranic vein, “How can we say that he is not a man in the world like us when we see him sitting on the couch and eating and drinking and walking about?”

And the child replied, “Let’s talk about something else.”

And yet any mention of devotees is invidious because there are always others who could be mentioned. For instance, few spoke with Sri Bhagavan more freely than Devaraja Mudaliar or than T.P. Ramachandra Aiyar, whose grandfather had once taken the young Sri Ramana by main force to a ceremonial meal in his house — the only house in which he ever took food after his arrival at Tiruvannamalai. Many beautiful pictures of Sri Bhagavan, showing incredible variety of expression, were taken by Dr. T.N. Krishnaswami, who used to come on occasional visits from Madras. Some of the most vivid and delightful accounts of incidents at the Ashram, breathing the charm of Sri Bhagavan’s presence, are contained in letters written in Telugu by a lady devotee, Nagamma, to her brother D.S. Sastry, a bank manager at Madras. Again, there were devotees who seldom or never found it necessary to speak to Sri Bhagavan. There were householders who came whenever occasion permitted from whatever town or country their destiny had placed them in and others who paid one short visit and remained thenceforth disciples of the Master though not in his physical presence. And some there were who never saw him but received the silent initiation from a distance.

Sri Bhagavan discouraged anything eccentric in dress or behaviour and any display of ecstasy. It has already been shown how he disapproved of the desire for visions and powers and how he preferred householders to strive in the conditions of family and professional life. He evoked no spectacular changes in the devotees, for such changes may be a superstructure without foundation and collapse later. Indeed, it sometimes happened that a devotee would grow despondent, seeing no improvement at all in himself and would complain that he was not progressing. In such cases Sri Bhagavan might offer consolation or he might retort, “How do you know there is no progress?” And he would explain that it is the Guru not the disciple who sees the progress made; it is for the disciple to carry on perseveringly with his work even though the structure being raised may be out of sight of the mind. It may sound a hard path, but the disciples’ love for Bhagavan and the graciousness of his smile gave it beauty.

Any exaggerated course such as mouna or silence was also discouraged. On at least one occasion Sri Bhagavan made this very clear. Hearing that Major Chadwick intended to go mouni next day, he spoke at length against the practice, pointing out that speech is a safety valve and that it is better to control it than to renounce it, and making fun of people who give up speaking with their tongue and speak with a pencil instead. The real mouna is in the heart and it is possible to remain silent in the midst of speech just as it is to remain solitary in the midst of people.

Sometimes, it is true, there was exaggeration. In accordance with the concealed nature of his upadesa, explained in a previous chapter, Sri Bhagavan would seldom explicitly bid or forbid, and yet those who embarked on any exaggerated course must have felt his disapproval, even if they did not admit it to themselves, for they almost invariably began absenting themselves from the hall. I recollect one such case where the mental balance was threatened and Sri Bhagavan said explicitly, “Why does she not come to me?” One has to know how scrupulously he avoided giving explicit instructions or telling anyone to come or go, how skilfully he parried any attempt to manoeuvre him into doing so, how binding and how precious the slightest indication of his will was considered, in order to appreciate the significance of such a saying.

In this case the devotee did not come and shortly afterwards her mind was unhinged. This was not the only instance. Despite the air of normality, the terrific force radiating from Sri Bhagavan was too potent for some who came. It was noticeable that, in any such case, as soon as the mental balance had been destroyed the person would cease to seclude himself and begin coming to the Ashram. It was also noticeable that Sri Bhagavan would sometimes scold such a person like a naughty child who had permitted himself some indulgence that he could and should have resisted. In a fairly high proportion of cases, a fight began to be put up under his influence and the sufferer struggled back to normality.

Although such cases have to be mentioned in order to complete the picture, it should not be imagined, from the space bestowed on them, that they were at all frequent. They always remained rare.

It is hard to postulate anything definite about the methods of Sri Bhagavan because exceptions can often be found. There were cases when his instructions were explicit, especially if one could approach him alone. Anantanarayan Rao, a retired veterinary surgeon who had built a house near the Ashram, had several times been summoned urgently to Madras where his brother-in-law was seriously ill. On one occasion he received a telegram to this effect and, although it was late in the evening, took it straight to Sri Bhagavan. Previously he had never paid much attention, but this time he said, “Yes, yes, you must go.” And he began speaking of the unimportance of death. Rao went home and told his wife that this time the disease must be fatal. They reached Madras a couple of days before his brother-in-law passed away.

One heard occasionally of more dynamic instances also, such as a devotee being instructed to use the name ‘Ramana’ as an invocation, but they were never much spoken about.

Usually a devotee would himself take a decision and then announce it tentatively. The deciding was a part of his sadhana. If it was rightly done there would be a smile of approval that made the heart sing, perhaps a brief verbal consent. If the decision was not approved that also would usually be visible. A householder once announced his decision to leave Tiruvannamalai for some other town where he could get a better paid job. Sri Bhagavan laughed, “Everyone is free to make plans.” The plan did not come off.

When one of India’s political leaders went to Madras to hold meetings an attendant who was an admirer of his asked leave to go there. Sri Bhagavan sat with a face like stone, as though he had not heard. Nevertheless the attendant went. He rushed from meeting to meeting, arriving always too late or failing to obtain admission. And when he got back Sri Bhagavan teased him about it. “So you went to Madras without permission? Did you have a successful trip?” So completely devoid of ego was he that he could talk or joke about his own actions as naturally and impersonally as about those of anyone else.

The influence of Sri Bhagavan was to turn one from the pleasure and pain, the hope and anxiety, that are caused by circumstances to the inner happiness that is one’s true nature and, realizing this, there were devotees who never asked for anything, even in mental prayer, but strove instead to overcome the attachment that gives rise to wishes. Even though they had not completely succeeded, it would have seemed a sort of betrayal to go to Sri Bhagavan with a request for outer benefits, for anything but greater love, greater steadfastness, greater understanding. If afflictions came, the method was not to seek to get them removed but to ask, ‘to whom is this affliction? Who am I?’ and thus draw nearer to conscious identity with That which suffers neither birth nor death nor any affliction. And if any turned to Sri Bhagavan with that intention peace and strength would flow into him.

Human nature being what it is, there were also devotees who did ask Sri Bhagavan for help and protection in the events of life. Taking a different point of view, they looked upon him as their father and mother and turned to him whenever any trouble or danger threatened. Either they would write a letter telling him about it or simply pray to him, wherever they might be. And their prayers were answered. The trouble or danger would be averted or, in cases where that was not possible or beneficial, peace and fortitude would flow into them to endure it. Help came to them spontaneously, with no volitional intervention on the part of Sri Bhagavan. That does not mean that it was due merely to the faith of the devotee; it was due to the Grace that emanated from him in response to the faith of the devotee.

Some devotees were puzzled by this use of power without volition and sometimes even without mental knowledge of the conditions. Devaraja Mudaliar has recorded how he once questioned Sri Bhagavan about it.

“If, in the case of Bhagavan as in that of all Jnanis, the mind has been destroyed and he sees no bheda (otherness) but only the One Self, how can he deal with each separate disciple or devotee and feel for him or do anything for him?” I asked Bhagavan about this and added: ‘It is evident to me and many others with me here that when we intensely feel about any of our troubles and appeal to Bhagavan mentally from wherever we happen to be help comes almost instantaneously. A man comes to Bhagavan, some old devotee of his. He proceeds to relate all sorts of troubles he has had since he last met Bhagavan; Bhagavan listens to his story patiently and sympathetically, occasionally even expressing wonder and interjecting, ‘Oh! is that so?’ and so on. The story often ends: ‘When all else failed I finally appealed to Bhagavan and Bhagavan alone saved me.’ Bhagavan listens to all this as though it was news to him and even tells others who come later, ‘It seems such and such things have happened to so and so since he was last with us.’ We know that Bhagavan never pretends, so he is apparently not aware of all that has happened, at least on one plane, until he is told. At the same time, it is clear to us that the moment we are in anguish and cry for help he hears us and sends help in one way or another, at least by giving fortitude or other facilities for bearing the trouble that has descended on us if for some reason it cannot be averted or modified. When I put all this to Bhagavan he replied, ‘Yes, all that happens automatically’.”

It was very rarely that Sri Bhagavan deliberately used supernatural powers. Moreover if he did so it was as concealed as his initiation and upadesa. In the later years there was one householder among the attendants, a Rajagopala Aiyar. He had a son of about three who had been given the name of Ramana, a pleasant little fellow who used to run and prostrate to Sri Bhagavan daily. One evening, after the devotees had dispersed for the night, the child was bitten by a snake. Rajagopala Aiyar picked him up and ran straight to the hall. Even so the child was already blue and gasping by the time he got there. Sri Bhagavan passed his hands over him and said, “You are all right, Ramana.” And he was all right. Rajagopala Aiyar told a few of the devotees but it was not much talked about.

Although they shade into one another, a distinction has to be drawn between asking for boons and relying on Sri Bhagavan for one’s protection and welfare. The latter he certainly approved of. If any cast the burden of their welfare on him he accepted it. In Aksharamanamalai he wrote, depicting the attitude of the disciple to the Guru: “Didst Thou not call me in? I have come in and my maintenance is now Thy burden.” He once, on the request of a devotee, selected forty-two verses from the Bhagavad Gita and arranged them in a different sequence to express his teaching, and among them was the verse, “I undertake to protect and secure the welfare of those who, without otherness, meditate on Me and worship Me and ever abide thus attuned.” There may be severe trials and periods of faith-testing insecurity, but a devotee who puts his trust in Sri Bhagavan is always looked after.