Chapter 11 of the biography “Ramana Maharshi And The Path Of Self-Knowledge” written by Arthur Osborne.

It is held in Hinduism (as expounded, for instance, by Shankaracharya in his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, Ch. V, vv. 40-44) that after death one who has not dissolved the illusion of a separate individuality in realization of identity with the Self passes on to a state of heaven or hell according to the good or bad karma or balance-sheet he has accumulated during his earth-life, and that, after the exhaustion of this harvest-time, he again returns to earth, to a high or low birth in conformity with his karma, in order to work out that part of it known as prarabdha, that is to say the destiny of one lifetime. During his new earth-life he again accumulates agamya or new karma, and this is added on to his sanchitha-karma or that residue of his already accumulated karma which is not prarabdha.

It is commonly held that progress can be made and karma worked off only during a human life; however Sri Bhagavan has indicated that it is possible for animals also to be working off their karma. In a conversation quoted in this chapter he said, “We do not know what souls may be tenanting these bodies and for finishing what part of their unfinished karma they may seek our company.” Shankaracharya also affirmed that animals can attain Liberation. Moreover, one of the Puranas tells how the Sage Jada-Bharata was assailed while dying by a fleeting thought of his tame deer and had to be born again as a deer in order to exorcise this last remaining attachment.

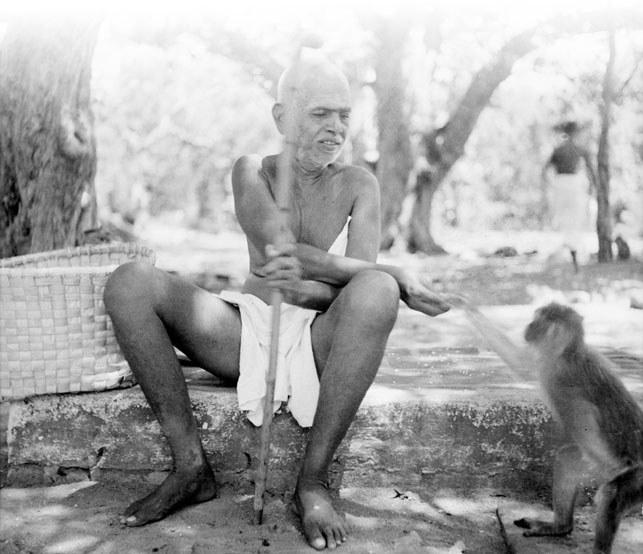

Sri Bhagavan showed the same consideration to the animals whom destiny had brought into contact with him as to the people. And animals were no less attracted to him than people. Already at Gurumurtam birds and squirrels used to build their nests around him. In those days devotees supposed that he was as oblivious to the world as he was unattached to it, but in fact he was keenly observant and he has since told of a squirrel family that occupied a nest abandoned there by some birds.

He never referred to an animal in the normal Tamil style as ‘it’ but always as ‘he’ or ‘she’. “Have the lads been given their food?” — and it would be the Ashram dogs he was referring to. “Give Lakshmi her rice at once” — and it was the cow Lakshmi that he meant. It was a regular Ashram rule that at meal-time the dogs were fed first, then any beggars who came, and last the devotees. Knowing Sri Bhagavan’s reluctance to accept anything that is not shared by all alike, I was surprised once to see him tasting a mango between meals, and then I saw the reason — the mango season was just beginning and he wanted to see whether it was ripe enough to give to the white peacock that had been sent from the Maharani of Baroda and had become his ward. There were other peacocks also. He would call to them, imitating their cry, and they would come to him and receive peanuts, rice, mango. On the last day before his physical death, when the doctors said the pain must be frightful, he heard a peacock screech on a nearby tree and asked whether they had received their food.

Squirrels used to hop through the window on to his couch and he would always keep a little tin of peanuts beside him for them. Sometimes he would hand a visiting squirrel the tin and let it help itself; sometimes he would hold out a nut and the little creature would take it from his hand. One day, when, on account of his age and rheumatism, he had begun to walk with the aid of a staff, he was descending the few steps into the Ashram compound when a squirrel ran past his feet, chased by a dog. He called out to the dog and threw his staff between them, and in doing so he slipped and broke his collar-bone; but the dog was distracted and the squirrel saved.

The animals felt his Grace. If a wild animal is cared for by people its own kind boycott it on its return to them, but if it came from him they did not; rather they seemed to honour it. They felt the complete absence of fear and anger in him. He was sitting on the hillside when a snake crawled over his legs. He neither moved nor showed any alarm. A devotee asked him what it felt like to have a snake pass over one and, laughing he replied “Cool and soft.”

He would not have snakes killed where he resided. “We have come to their home and have no right to trouble or disturb them. They do not molest us.” And they didn’t. Once his mother was frightened when a cobra approached her. Sri Bhagavan walked towards it and it turned and went away. It passed between two rocks and he followed it; however, the passage ended against a rock-wall and, being unable to escape, it turned and coiled its body and looked at him. He also looked. This continued for some minutes and then the cobra uncoiled and, feeling no more need for fear, crawled quietly away, passing quite close to his feet.

Once when he was sitting with some devotees at Skandashram a mongoose ran up to him and sat for awhile on his lap. “Who knows why it came?” he said. “It could have been no ordinary mongoose.” There is another case of a far from ordinary mongoose told by Professor Venkatramiah in his diary. In answer to a question by Mr. Grant Duff, Sri Bhagavan said:

“It was on the occasion of Arudra Darshan (a Saivite festival). I was then living on the Hill at Skandashram. Streams of visitors were climbing up the Hill from the town and a mongoose, uncommonly large and of a golden hue, not the usual grey colour, and without the usual black spot on its tail, passed fearlessly through the crowds. People thought it was a tame one and that its owner must be among the crowd. It went straight up to Palaniswami, who was taking a bath in the spring byVirupaksha Cave. He stroked the creature and patted it. It followed him into the cave, inspected every nook and corner of it, and then joined the crowd to pass up to Skandashram. Everyone was struck by its attractive appearance and fearless movements. It came to me, climbed on to my lap, and rested there for some time. Then it raised itself up, looked around and moved down. It went around the whole place and I followed it lest it should be harmed by careless visitors or by the peacocks. Two peacocks did look at it inquisitively, but it moved calmly from place to place until finally it disappeared among the rocks to the south-east of the Ashram.”

Once Sri Bhagavan was cutting up vegetables for the Ashram kitchen in the early morning before sunrise, together with two devotees. One of them, Lakshmana Sharma, had brought his dog with him — a handsome, pure white dog — and it was dashing about in high spirits and refused the food offered to it. Sri Bhagavan said: “You see what joy he shows? He is a high soul who has taken on this canine form.”

Professor Venkatramiah has told in his diary of a remarkable case of devotion in the Ashram dogs:

“At that time (i.e. in 1924) there were four dogs in the Ashram. Sri Bhagavan said that they would not accept any food unless he himself had partaken of it. The pandit put this to the test by spreading some food before them, but they would not touch it. After awhile Sri Bhagavan put a morsel of it into his mouth and immediately they fell upon it and devoured it.”

The ancestress of most of the Ashram dogs was Kamala, who came to Skandashram as a puppy. The devotees tried to drive her away, fearing that she would litter the Ashram with pups year after year, but she refused to go. A large canine family did indeed grow up, but they all had to be treated with equal consideration. On the occasion of her first delivery, Kamala was given her bath, painted with turmeric, decked with vermilion on the forehead and given a clean place in the Ashram where she remained for ten days with her pups. And on the tenth day her purification was celebrated with regular feasting. She was an intelligent and serviceable dog. Sri Bhagavan would often depute her to take a newcomer round the Hill. “Kamala, take this stranger round”; and she would guide him to every image, tank and shrine around the hill.

One of the most remarkable of the dogs, though not of Kamala’s progeny, was Chinna Karuppan (Little Blackie). Sri Bhagavan himself has given an account of him. “Chinna Karuppan was pure black all over, whence his name. He was a person of high principles. When we were in Virupaksha Cave something black used to pass us at a distance. We would sometimes see his head peeping over the bushes. His vairagya (dispassion) seemed to be very strong. He kept company with none, and in fact seemed to avoid company. We respected his independence and vairagya and used to leave food near his place and go away. One day, as we were going up, Karuppan suddenly jumped across the path and romped upon me, wagging his tail in glee. How he singled me out from the group for his display of affection was the wonder. Thereafter he remained with us in the Ashram as one of the inmates. A very intelligent and serviceable fellow he was, and how high-minded! He had lost all his former aloofness and became very affectionate. It was a case of universal brotherhood. He would make friends with every visitor and inmate, climb on to his lap and nestle against him. His overtures were generally well received. A few tried to avoid him but he was indefatigable in his efforts and would take no refusal as final. However, if he was ordered away he would obey like a monk observing the vow of obedience. Once he went near an orthodox Brahmin who was reciting mantras at the foot of a bel-tree near our cave. The Brahmin regarded dogs as unclean and scrupulously avoided contact or even proximity to them. However, Karuppan, evidently understanding and observing only the natural law of equality (samatvam), insisted on going near him. Out of consideration for the Brahmin’s feelings an inmate of the Ashram raised his stick and beat the dog, though not hard. Karuppan wailed and ran away and never returned to the Ashram, nor was seen again. He would never again approach a place where he had been once ill-treated, so sensitive he was.

“The person who made this mistake evidently underrated the dog’s principles and sensitivity. And yet there had already been a warning. It was like this. Palaniswami had once spoken and behaved rudely to Chinna Karuppan. It was a cold, rainy night, but all the same Chinna Karuppan left the premises and spent the whole night on a bag of charcoal some distance away. It was only in the morning that he was brought back. There had also been a warning from the behaviour of another dog. Some years back Palaniswami scolded a small dog that was with us at Virupaksha Cave and the dog ran straight down to Sankhatirtham Tank and soon after his dead body was floating there. Palaniswami and all the others at the Ashram were at once told that dogs and other animal inmates of the Ashram have intelligence and principles of their own and should not be treated roughly. We do not know what souls may be tenanting these bodies and for finishing what portion of their unfinished karma they may seek our company.”

There were other dogs also that showed intelligence and high principles. While at Skandashram, Sri Bhagavan was usually beside one of the Ashram dogs when it breathed its last and the body was given a decent burial and a stone placed over the grave. In the later years, when the Ashram buildings had been put up and especially when Sri Bhagavan began to grow less active in body, the humans had it more their own way and animal devotees had little access.

Until the last few years monkeys still came to the window beside Sri Bhagavan’s couch and looked in through the bars. Sometimes one saw monkey mothers with the little ones clinging to them, as if to show them to Bhagavan, just as human mothers did. As a sort of compromise, the attendants were allowed to drive them away but were expected to throw them a banana before doing so.

Until he became too infirm, Sri Bhagavan walked on the Hill every morning after seven and every evening at about five o’clock. One evening, instead of the usual short walk, he went up to Skandashram. When he did not return at the usual time, some devotees followed him up the Hillside, others gathered in small clusters, discussing where he had gone, what it meant, and what to do about it, others sat in the hall, waiting. A pair of monkeys came to the hall door and, forgetting their fear of people, stepped inside and looked anxiously at the empty couch.

After that, a few years before humans also lost their sight of Sri Bhagavan on earth, the day of the monkeys was finished. The palm-leaf roofs outside the hall were extended, making access more difficult for them, and anyway most of them were taken back to the jungle or captured by the municipality and sent to America to be experimented on.

From 1900, when Sri Bhagavan first went to live on the Hill, to 1922, when he came down to the Ashram at its foot, he was very intimate with the monkeys. He watched them closely, with the love and sympathy that the Jnani (Sage) has for all beings and with that keen observation that was natural to him. He learnt to understand their cries and got to know their code of behaviour and system of government. He discovered that each tribe has its king and its recognised district, and if another tribe infringes on this there will be war. But before starting a war or making peace an ambassador is sent from one tribe to the other. He would tell visitors that he was recognised by the monkeys as one of their community and accepted as arbiter in their disputes.

“Monkeys, as a rule, would boycott one of their group if he had been cared for by people, but they make an exception in my case. Also, when there is misunderstanding and quarrelling they come to me and I pacify them by pushing them apart and so stop their quarrelling. A young monkey was once bitten by an elder member of his group and left helpless near the Ashram. The little fellow came limping to the Ashram at Virupaksha Cave, hence we called him Nondi (the Lame). When his group came along five days later they saw that he was tended by me but still they took him back. From then on they would all come to get any little thing that could be spared for them outside the Ashram, but Nondi would come right on to my lap. He was a scrupulously clean eater. When a leaf-plate of rice was set before him he would not spill a single grain of rice outside it. If he ever did spill any he would pick it up and eat it before going on with what was on the plate.

“He was very sensitive though. Once, for some reason, he threw out some food and I scolded him…. ‘What! Why are you wasting food?’ He at once hit me over the eye and hurt me slightly. As a punishment he was not allowed to come to me and climb on to my lap for some days, but the little fellow cringed and begged hard and regained his happy seat. That was his second offence. On the first occasion I put his cup of hot milk to my lips to blow it, so as to cool it for him, and he was annoyed and hit me over the eye, but there was no serious hurt and he at once came back to my lap and cringed as though to say, ‘Forget and forgive’, so he was excused.”

Later on Nondi became king of his tribe. Sri Bhagavan also told of another monkey king who took the bold step of outlawing two turbulent males in his tribe. The tribe thereupon became restive and the king left them and went alone into the jungle where he remained for two weeks. When he returned he challenged the critics and rebels, and so strong had he become through his two weeks tapas (privation) that none dared answer his challenge.

Early one morning it was reported that a monkey lay dying near the Ashram. Sri Bhagavan went to see and it was this king. It was brought to the Ashram and lay supporting itself against Sri Bhagavan. The two exiled males were sitting on a tree nearby, watching. Sri Bhagavan moved to shift his weight and the dying monkey instinctively bit his leg. “I have four such marks of favour from monkey kings,” he said once, pointing to his leg. Then the monkey king uttered a last groan as he expired. The two watching monkeys jumped up and down and cried out with grief. The body was buried with the honours given to a sanyasin: it was bathed in milk and then in water and smeared with sacred ashes; a new cloth was placed over it leaving the face uncovered and camphor burnt before it. It was given a grave near the Ashram and over this a stone was raised.

One strange story of monkey gratitude is told. Sri Bhagavan was once walking round the foot of the Hill with a group of devotees and when they got near Pachaiamman Koil they felt hungry and thirsty. Immediately a tribe of monkeys climbed the wild fig trees at the roadside and shook the branches, strewing the road with the ripe fruit, and then ran away, not eating any themselves. And at the same time a group of women came up with earthen jars of water for drinking.

The most favoured of all the animal devotees of Sri Bhagavan was the cow Lakshmi. She was brought to the Ashram as a young calf together with her mother in 1926 by one Arunachala Pillai of Kumaramangalam near Gudiyatham and presented to Sri Bhagavan. He was reluctant to accept the gift as there was then no accommodation for cows at the Ashram. However, Arunachala Pillai absolutely refused to take them back and a devotee, Ramanath Dikshitar, offered to look after them, so they stayed. Dikshitar saw to their needs for about three months and then they were left with someone in town who kept cows. He kept them for about a year and then one day came to have darshan of Sri Bhagavan and brought them with him on a visit. The calf seems to have been irresistibly attracted to Sri Bhagavan and to have noted the way to the Ashram because she returned alone next day and from then on came every morning and returned to town only in the evening. Later, when she came to live in the Ashram, she would still come to Sri Bhagavan, going straight up to him and taking no notice of anyone else, and Sri Bhagavan would always have bananas or some other delicacy for her. For a long time she would come to the hall daily at lunchtime to accompany him to the dining hall, and so punctually that if he had been occupied by anything and sat beyond the hour he would look at the clock when she came in and find that it was time.

She bore a number of calves, at least three of them on Bhagavan’s Jayanthi (birthday). When a stone cow-house was built in the Ashram it was decided that Lakshmi should be the first to enter it on the day of its inauguration, but when the time came she could not be found; she had gone to lie by Sri Bhagavan and would not budge until he came too, so that he entered first and she behind him. Not only was she uncommonly devoted to Sri Bhagavan, but the Grace and kindness he showed her was quite exceptional. In later years there were a number of cows and bulls at the Ashram but no other that formed such an attachment or elicited such Grace. Lakshmi’s descendants are still there.

On June 17th, 1948, Lakshmi fell ill and on the morning of the 18th it seemed that her end was near. At ten o’clock Sri Bhagavan went to her. “Amma (Mother),” he said, “you want me to be near you?” He sat down beside her and took her head on his lap. He gazed into her eyes and placed his hand on her head as though giving her diksha (initiation) and also over her heart. Holding his cheek against hers, he caressed her. Satisfied that her heart was pure and free from all vasanas (latent tendencies) and centred wholly on Bhagavan, he took leave of her and went to the dining hall for lunch. Lakshmi was conscious up to the end; her eyes were calm. At eleven-thirty she left her body, quite peacefully. She was buried in the Ashram compound with full funeral rites, beside the graves of a deer, a crow and a dog which Sri Bhagavan had also caused to be buried there. A square stone was placed over her grave surmounted by a likeness of her. On the stone was engraved an epitaph that Sri Bhagavan had written stating that she had attained Mukti (Liberation). Devaraja Mudaliar asked Bhagavan whether that was used as a conventional phrase, as the phrase that someone has attained samadhi is a polite way of saying that he has died, or whether it really meant Mukti, and Sri Bhagavan said that it meant Mukti.