Chapter 13 of the biography “Ramana Maharshi And The Path Of Self-Knowledge” written by Arthur Osborne.

It is, perhaps, harder to visualise the Divine Man in the technique of daily living than in miracle or transfiguration, and for this a description of the routine of life during the last years will be helpful. The incidents that are fitted into it are no more noteworthy than many that went before, just as the devotees referred to are no more outstanding than many who remain unmentioned.

It is 1947 already. Fifty years have passed at Tiruvannamalai. With the onset of age and failing health, restrictions have been imposed and Sri Bhagavan is no longer accessible privately and at all hours. He sleeps on the couch where he gives darshan, the blessing of his Presence, during the day, but with closed doors now. At five o’clock the doors open and early morning devotees enter quietly, prostrate themselves before him and sit down on the black stone floor, worn smooth and shiny with use, many of them on small mats they have brought with them. Why did Sri Bhagavan, who was so modest, who insisted on equal treatment with the humblest, allow this prostration before him? Although humanly he refused all privileges, he recognised that adoration of the outwardly manifested Guru was helpful to sadhana, to spiritual progress. Not that outward forms of submission were sufficient. He once said explicitly, “Men prostrate themselves before me but I know who is submitted in his heart.”

A small group of Brahmins, resident at the Ashram, sit near the head of the couch and intone the Vedas; one or two others who have walked from the town, a mile and a half away, join them. At the foot of the couch incense-sticks are lit, diffusing their subtle perfume through the air. If it is in the winter months a brazier of burning charcoal stands beside the couch, a pathetic reminder of his failing vitality. Sometimes he warms his frail hands and thin tapering fingers, those exquisitely beautiful hands at the glow and rubs a little warmth into his limbs. All sit quietly mostly with eyes closed in meditation.

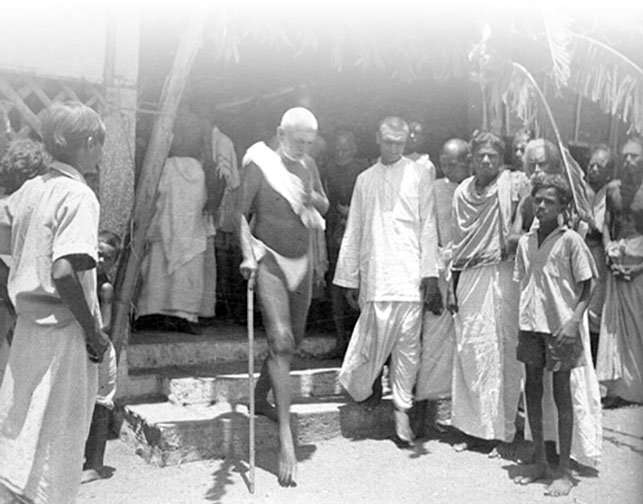

A few minutes before six the chanting ends. All rise and stand as Sri Bhagavan raises himself with an effort from the couch, reaches out for the staff that the attendant places in his hand, and walks with slow steps to the door. It is not from weakness or fear of falling that he walks with downcast gaze; one feels that it is an innate modesty. He leaves the hall by its north door, on the side of the Hill, and passes slowly, leaning on his staff and a little bent, along the passage between the white-walled dining hall and office building, then, skirting the men’s guest house, to the bathroom beside the cowshed, farthest east of the Ashram buildings. Two attendants follow him, stocky, short and dark and wearing white dhoties down to the ankles, while he is tall and slim and golden-hued and clad only in a white loincloth. Only occasionally he looks up if some devotee approaches him or to smile upon some child.

There is no way of describing the radiance of his smile. One who might appear a hardened businessman would leave Tiruvannamalai with a lilt in his heart from that smile. A simple woman said: “I don’t understand the philosophy but when he smiles at me I feel safe, just like a child in its mother’s arms. I had never yet seen him when I received a letter from my fiveyear-old daughter: ‘You will love Bhagavan. When he smiles everyone must be so happy’.”

Breakfast is at seven. After breakfast Sri Bhagavan goes for a short walk and then returns to the hall. In the interval it has been swept out and clean covers placed on the couch, some of them richly embroidered, being presents from devotees. All are spotlessly clean and very carefully folded, for the attendants know how observant he is and how every little detail will be noticed, whether it is remarked upon or not.

By eight o’clock Sri Bhagavan is back in the hall and the devotees begin to arrive. By nine the hall is full. If you are a newcomer you probably feel how intimate the hall is, how close you are to the Master, for the entire space is only 40 feet by 15. It runs east and west with a door in each long side. That on the north, facing the Hill, opens out on to a tree-shaded square with the dining hall running along its eastern side and on its west the garden and dispensary. That on the south leads out to the temple and, beyond it, the road, the side from which the devotees arrive. The couch is at the northeast of the hall. Beside it is a revolving bookcase containing the books most frequently in demand, and on it stands a clock, while another hangs on the wall beside the couch, both right to the minute.

If any book is needed for reference Sri Bhagavan will know just where it stands, on which shelf, and probably the very page of the passage to be referred to. Large bookcases with glass-panelled doors stand along the south wall.

Most of the devotees sit in the body of the hall, facing Sri Bhagavan, that is facing east, the women in front of him, down the northern half of the hall, the men to his left. Only a few of the men sit alongside the couch, with their backs to the south wall and nearer to Sri Bhagavan than the others. A few years previously it was the women who had this privilege and then, for some reason, the positions were changed. It is the Hindu tradition for men and women to sit apart and Sri Bhagavan approves of it, as the magnetism between them may disturb the greater spiritual magnetism.

Again the incense sticks are burning. Some there are, now also, who sit with eyes closed in meditation, but others relax and simply feast their eyes on Sri Bhagavan. A visitor sings songs of praise that he has composed. One who has been away and is returning, offers a tribute of fruit at his feet, and then finds a place in the seated ranks before him. An attendant gives back a part of the offering as the grace or prasadam of Sri Bhagavan; something may be given to children who enter the hall, to monkeys who stand at the window near the couch or peer round the door, to the peacocks, or to the cow Lakshmi if she pays a visit. The rest is taken later to the dining hall to be shared among the devotees.

Sri Bhagavan accepts nothing for himself.There is an ineffable tenderness in his look. It is not only sympathy for the immediate troubles of his devotees but for the whole vast burden of samsara, of human life. And yet, despite the tenderness, the lines of his face can show the sternness of one who has conquered and never compromised. This aspect of hardness is usually covered by a soft growth of white hair, for, as a sanyasin, his head and face are shaved every full moon day. Many of the devotees regret it the growth of white hair on face and head so enhances the grace and gentleness of aspect but none presumes to mention it to him.

His face is like the face of water, always changing, yet always the same. It is amazing how swiftly it moves from gentleness to rock-like grandeur, from laughter to compassion. So completely does each successive aspect live that one feels it is not one man’s face but the face of all mankind. Technically he may not be beautiful, for the features are not regular; and yet the most beautiful face looks trivial beside him. Such reality is in his face that its impress sinks deep in the memory and abides when others fade. Even those who have seen him only for a short time or only in a photograph recall him to their mind’s eye more vividly than those they know well. Indeed, it may be that the love, the grace, the wisdom, the deep understanding, the childlike innocence that shines from such a picture is a better starting point for meditation than any words.

Around the couch, a couple of feet away from it, is a movable railing about eighteen inches high. That caused a little controversy at first. The Ashram management observed how Sri Bhagavan normally avoided being touched and drew back if any made to do so. Recollecting, moreover, how a misguided devotee had once broken a coconut and wanted to honour him by pouring the milk over his head, they decided that so much seclusion would be better. Many of the devotees, on the other hand, felt that it was placing a sort of barrier between them and Sri Bhagavan. The discussion as to whether he approved of this went on in front of him, but none presumed to ask him for a decision. Bhagavan sat unaffected.

Some of the devotees, without rising from their places, talk with Sri Bhagavan about themselves or their friends, give news of absent devotees, ask doctrinal questions. One feels the homely atmosphere, as of a great family. Perhaps someone has a private matter to report and goes up to the couch to speak to Sri Bhagavan in an undertone or to hand him a paper on which he has written it out. It may be that he wants an answer or that it is enough simply to inform Sri Bhagavan and he has faith that all will be well.

A mother brings a little child in and he smiles to it more beautifully than a mother. A little girl brings her doll and makes it prostrate before the couch and then shows it to Bhagavan who takes it and looks at it. A young monkey slips in at the door and tries to grab a banana. The attendant chases it out, but there happens to be only one attendant present, so it runs round the end of the hall and in through the other door and Sri Bhagavan whispers urgently to it: “Hurry! Hurry! He’ll be back soon.” A wild-looking sadhu with matted locks and ochre robe stands with hands upraised before the couch. A prosperous townsman in a European suit makes a decorous prostration and secures a front seat; his companion, not quite sure of his devotion, does not prostrate at all.

A group of pandits sit near the couch, translating a Sanskrit work, and from time to time take it up to him to elucidate some point. A three-year-old, not to be outdone, takes up his story of Little Bo Peep, and Sri Bhagavan takes that too, just as graciously, and looks through it with the same interest; but it is tattered, so he passes it to an attendant to bind and gives it back next day neatly repaired.

The attendant is painstaking in his work. He needs to be because Sri Bhagavan himself is keen of eye and hand and will pass no slovenly work. The attendants feel that they enjoy the especial Grace of Sri Bhagavan. So do the pandits. So does the three-year-old. One gradually perceives how the profound immediacy of response leads devotees utterly varied in mind and character to feel a special personal intimacy with the Master.

Gradually also one perceives something of the skill and subtlety of Sri Bhagavan’s guidance — or rather of the human manipulation of his guidance, for the guidance itself is invisible. All are open books to him. He casts a penetrating glance at this disciple or that to see how his meditation is progressing; occasionally his eyes rest full upon one of them, transmitting the direct force of his Grace. And yet all this is kept as inconspicuous as possible: a glance may even be sidelong to avoid attention, a more steadfast look may be in the interval of reading a newspaper or when the recipient himself is sitting with closed eyes and unaware; this may be to guard against the twofold danger of jealousy in other devotees and conceit in the one favoured with his look.

Special attention is often shown to a newcomer — to that the devotees have grown accustomed. Perhaps a smile will greet him every time he enters the hall, he will be watched in meditation, encouraged with friendly remarks. This may continue for a few days or weeks or months, until the meditation has been kindled in his heart or until he is bound by love to Sri Bhagavan. But such is human nature that the ego also has probably fed on the attention and he has begun to ascribe it to a superiority over the other devotees that he and Sri Bhagavan alone perceive. And then he will be ignored for a while until a deeper understanding evokes a deeper response. Unfortunately, this does not always happen; sometimes the pride in a fancied pre-eminence with Sri Bhagavan remains.

At about eight-thirty the newspapers are brought in to Sri Bhagavan and unless any questions are being asked he will open some and look through them, perhaps remarking on any item of interest — though never in a way that could be taken as a political opinion. Some of the papers are sent to the Ashram itself; some are ordered privately by one devotee or another and passed on to Sri Bhagavan first, just for the pleasure of reading a paper he has touched. One can see when it is a privately-owned paper because he will slip it carefully and deftly out of its wrapper and back again after reading, so that the owner shall receive it in the same condition that it arrived.

From about ten minutes to ten till about ten past Sri Bhagavan used to walk on the Hill, but during these last few years his body is too infirm and he just walks across the Ashram ground. All rise as he leaves the hall, unless any is deep in meditation. During this recess they gather and talk in little clusters — men and women together, for it is only while sitting in the hall that they are separate. Some read their newspapers; others get their mail from Raja Iyer, the keen, serviceable little postmaster who knows everything about everybody.

Sri Bhagavan re-enters, and if those who are sitting in the hall make to rise he motions them to remain sitting. “If you get up when I enter you will have to get up for every person who enters.” Once, during the hot months, an electric fan was put on the window sill beside him. He ordered the attendant to switch it off, and when the latter persisted he himself reached up and pulled out the plug. The devotees were just as hot; why should he alone have a fan? Later, ceiling fans were installed and all benefited alike.

The mail is now brought to Sri Bhagavan. A letter addressed simply ‘The Maharshi, India’. A packet of flower seeds from a devotee in America to sow in the Ashram garden. Letters from devotees all over the world. Sri Bhagavan reads through each one carefully, even scrutinising the address and postmark. If it is news from any devotee who has friends in the hall he will tell them it. He himself does not answer letters. This expresses the standpoint of the Jnani (Enlightened One), not having relationships, not having a name to sign. Answers are written in the Ashram office and submitted to him in the afternoon when he will point out if there is anything inappropriate in them. If anything particular or personal is needed in the answer he may indicate it, but on the whole his teaching is so plain that a devotee easily learns to reiterate it verbally— it is the Grace behind the words that he alone can give.

After the letters are disposed of it may be that all sit silent, but there is no tension in the silence; it is vibrant with peace. Perhaps someone comes to take leave, some lady with tears in her eyes at having to go, and the luminous eyes of Bhagavan infuse love and strength. How can one describe those eyes? Looking into them one feels that all the world’s misery, all the struggle of one’s past, all the problems of the mind, fall away like a miasma from which one has been lifted into the calm reality of peace. There is no need for words; his Grace stirs one’s heart and thus the outer Guru turns one inwards to awareness of the Guru within.

At eleven o’clock the Ashram gong sounds for lunch. All stand up until Sri Bhagavan has left the hall. If it is an ordinary day the devotees disperse to their homes, but perhaps it is some festival or a bhiksha given by one of the devotees as an offering or thanksgiving and all are invited to lunch. The large dining hall is completely bare of furniture. Pieces of banana leaf are spread out as plates in double rows breadthwise across the red-tiled floor and the devotees sit cross-legged before them. A partition in the middle stretches three-quarters of the width of the hall. At one side of it sit those Brahmins who prefer to retain their orthodoxy, at the other side non-Brahmins, non-Hindus and those Brahmins who prefer to eat with the other devotees. Provision is thus made for the orthodox, but Sri Bhagavan says nothing to induce Brahmins either to retain or discard their orthodoxy, at any rate not publicly or to all alike. He himself sits against the east wall in sight of both sections of the devotees.

Attendants and Brahmin women walk down the rows serving rice, vegetables and condiments on the leaves. All wait for Sri Bhagavan to start eating and he waits until everyone has been served. Eating is a full-time occupation, not mixed with chatter, as in the West. An American lady who finds it hard to conform to Indian customs has brought a spoon with her. One of the servers piles some vegetables on her leaf and tells her that they have been specially prepared without the hot spices used in the general cooking — Sri Bhagavan himself gave instructions for it. The rest all eat busily with their hands. Attendants pass up and down the rows, serving second helpings, water, buttermilk, fruit or sweet. Sri Bhagavan calls an attendant back to him angrily. When there is remissness in the outer technique of life he can show anger. The attendant is putting a quarter mango on every leaf and has slipped a half mango on to his. He puts it back and picks out the smallest piece he can see.

One by one the diners finish, and as each one finishes he rises and leaves, stopping to wash his hands at the tap outside before he goes home.

Until two o’clock Sri Bhagavan rests and the hall is closed to devotees. The Ashram management decided that his failing health made this midday rest necessary, but how were they to bring it about? If asked to accept an indulgence that would inconvenience the devotees he would most probably refuse. Rather than risk this they decided to make the change unofficially by privately requesting devotees not to enter the hall at that time. For a few days all went well and then a newcomer, not knowing the rule, went in after lunch. An attendant beckoned to him to come out, but Sri Bhagavan called him back to ask what it was all about. After lunch next day Sri Bhagavan was seen sitting on the steps outside the hall and when the attendant asked him what was the matter he said, “It seems that no one is allowed into the hall until two o’clock.” It was only with great difficulty that he was prevailed upon to accept the hours of rest.

In the afternoon there may be new faces in the hall, for few of the devotees sit the whole day there. Even those who live near the Ashram usually have household or other tasks to see to and many have their fixed hours of attendance.

Sri Bhagavan never speaks about doctrine except in answer to a question, or only very rarely. And when he is answering questions it is not in a tone of pontifical gravity but in a conversational manner, often with wit and laughter. Nor is the questioner expected to accept anything because he says it; he is free to dispute until convinced. A Theosophist asks whether Sri Bhagavan approves of the search for invisible Masters and he retorts with swift wit, “If they are invisible how can you see them?” “In consciousness,” the Theosophist replies, and then comes the real answer, “In consciousness there are no others.”

Someone from another ashram asks, “Am I right in saying that the difference is that you don’t ascribe reality to the world and we do?”

And Sri Bhagavan uses humour to avert discussion. “On the contrary, since we say that Being is One we ascribe full reality to the world, and what is more we ascribe full reality to God: but by saying there are three you only give one-third reality to the world, and you only give one-third reality to God.”

Everyone joins in the laughter, but in spite of this some of the devotees drift into a discussion with the visitor, and then Sri Bhagavan remarks, “There is not much benefit in such discussions.”

If questions are put in English he replies through an interpreter. Though he does not speak English fluently he understands everything and pulls up the interpreter if there is the slightest inaccuracy.

Although doctrinally uniform, the replies of Sri Bhagavan were very much ad hominem, varying considerably with the questioner. A Christian missionary asked, “Is God personal?” and, without compromising with the doctrine of Advaita, Sri Bhagavan tried to make the answer easy for him: “Yes, He is always the First Person, the ‘I’ ever standing before you. If you give precedence to worldly things God seems to have receded into the background; if you give up all else and seek Him alone He alone will remain as the I, the Self.”

One wonders whether the missionary recalled that this is the name God proclaimed through Moses. Sri Bhagavan sometimes remarked on the excellence of ‘I Am’ as a Divine Name.

It is usually newcomers who ask questions and receive explanations. The disciples seldom have questions to ask, some of them never. The explanations are not the teaching; they are only a signpost to the teaching.

A quarter to five. Sri Bhagavan rubs his stiff knees and legs and reaches out for the staff. Sometimes it requires two or three efforts to rise from the couch, but he will not accept help. During the twenty minutes of his absence the hall is again swept out and the covers arranged on the couch.

Some ten or fifteen minutes after his return the chanting of the Vedas begins, followed by the Upadesa Saram, the ‘Instruction in Thirty Verses’ of Sri Bhagavan. This is one point in which Sri Bhagavan has discarded orthodoxy, for strictly speaking only Brahmins are allowed to listen to the chanting of the Vedas, whereas here all do alike. When asked what the benefit of it is he has replied simply, “The sound of the chanting helps to still the mind.” He has also said explicitly that it is not necessary to learn the meaning. This is a practical illustration of what has been said about the ‘meditation’ he enjoined — that it is not thought but turning the mind inwards to the awareness beyond thought.

The chanting lasts about thirty-five minutes. While it is going on it often happens that he sits still, his face eternal, motionless, majestic, as though carved in rock. When it is finished all sit till six-thirty when the ladies are expected to leave the Ashram. Some of the men remain for another hour, usually in silence, sometimes talking, singing Tamil songs; and then there is supper and the devotees disperse.

The evening session is particularly precious because it combines the solemnity of the early morning chanting with the friendliness of the later hours. And yet, for those who apprehend it, the solemnity is always there, even when Sri Bhagavan is outwardly laughing and joking.

An attendant comes to massage his legs with some liniment, but he takes it away from him. They fuss over him too much. But he turns the refusal into a joke: “You have had Grace by look and by speech and now you want Grace by touch? Let me have some of the Grace by touch myself.”

However, it is only a pale reflection of his humour that can be set down on paper, for it was less the things said, keen and witty though they were, than the saying of them. When he told a story he was a complete actor, reproducing the part as though he lived it. It was fascinating to watch him, even for those who did not understand the language. Real life also was a part he played and in real life the transitions could be just as swift, from humour to a deep sympathy.

Even in the early days, when he was thought to be oblivious to everything, he had a keen sense of humour, and there were jokes that he only told years later. On one occasion when his mother and a crowd of others visited him at Pavalakunru they bolted the door on the outside when they went into town for food, fearing that he might slip away. He, however, knew that the door could be lifted off its hinges and opened while still bolted, so in order to avoid the crowd and the disturbance he slipped out that way while they were gone. On their return they found the door shut and bolted but the room empty. Later, when no one was about, he returned the same way. They sat telling one another in front of him how he had disappeared through a closed door and then appeared again by means of siddhi (supernatural powers), and no tremor showed on his face, though years later the whole hall were shaking with laughter when he told them the story.

A word should be said also about the great annual festivals. Most of the devotees were unable to live permanently at Tiruvannamalai and could only come occasionally, so that there were always crowds for the public holidays, especially for the four great festivals of Kartikai, Deepavali, Mahapuja (the anniversary of the Mother’s death) and Jayanthi (the birthday of Sri Bhagavan). Jayanthi was the greatest and most heavily attended of these. At first Sri Bhagavan was reluctant to have it celebrated at all. He composed the stanzas:

You who wish to celebrate the birthday, seek first whence was your birth. One’s true birthday is when he enters. That which transcends birth and death — the Eternal Being.

At least on one’s birthday one should mourn one’s entry into this world (samsara). To glory in it and celebrate it is like delighting in and decorating a corpse. To seek

one’s Self and merge in the Self: that is wisdom.

However, for the devotees, the birth of Sri Bhagavan was cause for rejoicing and he was induced to submit; but he refused either then or on any occasion to allow puja (ritualistic worship) to be made to him. The crowd was vast and all the devotees took their meals with Sri Bhagavan that day. Even the large dining hall was inadequate; a palm leaf roofing was erected on bamboo supports over the square of ground outside and all sat there. There was also feeding of the poor, sometimes two or three relays coming to be fed, with police and boy scouts guarding the entrances and managing the crowds.

On any such day Sri Bhagavan would sit aloof, regal, and yet with an intimate look of recognition for each old devotee who came. At one of the Kartikai festivals, when the crowds packed the whole Ashram ground and a railing had been erected round him to keep them off, a little boy scrambled through the bars and ran up to him to show him his new toy. He turned to the attendant, laughing, “See how much use your railing is!”

In September 1946 a great celebration was held for the fiftieth anniversary of Sri Bhagavan’s arrival at Tiruvannamalai. Devotees gathered from far and wide. A Golden Jubilee Souvenir was compiled of articles and poems written for the occasion.

During the last years the old hall was becoming too small even on ordinary days, and it became more usual to sit outside under a palm leaf roofing. In 1939 work had started on a temple over the Mother’s samadhi, and this was completed in 1949, together with a new hall for Sri Bhagavan and the devotees to sit in. They were two parts of one building, constructed by traditional temple builders according to the sastraic (scriptural) rules.

The building stretches south of the old hall and the office, between them and the road. The western half of it, south of the old hall, is the temple, the eastern half is a large, square, well-ventilated hall where Sri Bhagavan was to sit with his devotees.

The kumbhabhishekam, or ritualistic opening of the temple and hall, was an imposing ceremony that many of the devotees attended. It crowned years of effort, work and planning. Sri Bhagavan, however, was reluctant to enter the new hall. He preferred simplicity and did not like any grandeur on his account. Many of the devotees also were reluctant — the old hall was so vibrant with his Presence and the new seemed cold and lifeless in comparison. When he entered it the last sickness had already gripped his body.